Alibaba, which filed for its IPO on May 6, isn’t just the “Amazon of China”—it’s also the Dropbox, PayPal, Uber, Hulu, ING Direct, and more. Though Google has its fingers in a similarly high volume of pies, its enterprises, unlike Alibaba’s, are exclusively digital.

Alibaba’s distinct businesses resemble more than a dozen major Western companies, by our count—a phenomenon we’ve sketched out in the graphic below. In the text that follows, we unravel some of that complexity—and explain how Alibaba has expanded on its way to a New York listing.

Following the ambitious vision of founder and chairman Jack Ma, Alibaba has recently gone on an investment bender, snatching up stakes in everything from mobile platforms to brick-and-mortar shopping malls, wealth-management products, and cloud services. This strategy might look scattershot. But Alibaba—a bit like Amazon, the Western company to which it’s most often compared—has demonstrated a knack for dominating whatever sector it enters and for anticipating what consumers want before they know they want it.

E-commerce platforms

Alibaba’s e-commerce platforms have historically made up the core of its business. Alibaba Group got its start with Alibaba.com, a B2B (business-to-business) site launched in 1999, which links foreign companies to Chinese manufacturers. After becoming profitable in 2002, Alibaba.com listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2007 (Alibaba Group took Alibaba.com private in 2012 due to both the group’s IPO plans and the stock’s poor performance in 2011).

Ma reinvested Alibaba.com’s profits in Taobao, a C2C (consumer-to-consumer) site that resembles eBay, which the company rolled out in 2003. The site proved wildly popular. To meet demand from businesses to sell their goods to consumers, Alibaba Group created Taobao Mall, which it spun off as its own domain, Tmall.com, in 2010. Within a year, Western brands like Gap and Ray-Ban had opened up storefronts on Tmall.

Both platforms are incredibly successful. For instance, on China’s Singles Day in November 2013—the equivalent of the US’s Cyber Monday—Tmall and Taobao customers spent $5.7 billion. While Alibaba makes money by charging Tmall vendors commission fees on transactions, its Taobao revenue comes from charging merchants to advertise.

Digital media

Tapping into Chinese social media is a critical part of Alibaba’s efforts to grow its e-commerce platforms. In 2013 it bought an 18% stake in the microblog Weibo—China’s largest, now with over 129 million monthly active users and penetration in almost all of the country’s urban areas—from its parent, Sina. Following Weibo’s public listing in New York last month, Alibaba’s stake was set to rise to 30%.

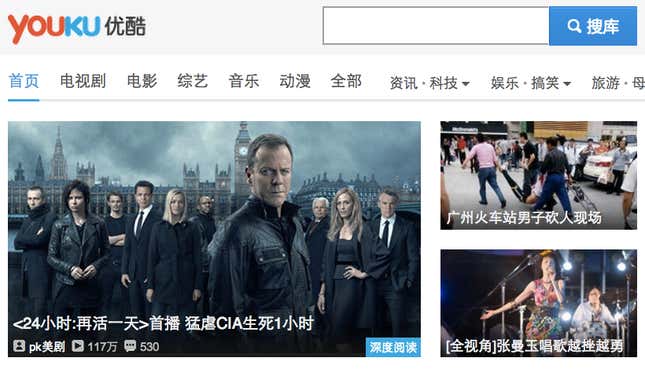

The deal makes sense particularly in China’s e-commerce market. Chinese shoppers are more likely than their US counterparts to follow brands online and purchase items through social media. Alibaba is also making a play for China’s quickly growing demand for online streaming—some 450 million people, or about 80% of the country’s internet users, watch television, movies and videos online. Alibaba recently shelled out $1.22 billion for a stake in the website Youku Tudou, the country’s largest online video platform—often compared to Youtube, which is banned in China. Other acquisitions include a controlling stake in ChinaVision Media Group, a television and film production company, and a 20% stake in Wasu Media, a Hangzhou-based online television firm.

Smartphones

Winning over the 500 million Chinese consumers who surf the web, shop, chat, invest, or play games primarily via their smartphones is arguably Alibaba’s most critical task. It faces competition from internet giant Tencent, whose widely used messaging app WeChat is already a platform for all of those functions. Alibaba’s answers to WeChat (and, to a degree, its US-based rival, WhatsApp) include messaging apps Laiwang and the California-based Tango, in which Alibaba has a minority stake.

Beyond messaging, Alibaba wants to worm its way into every aspect of Chinese smartphone users’ daily habits, which are still forming. Alibaba offers an app for booking a taxi, Kuaide Dache (literally, “quickly get a taxi”); AutoNavi, a maps app; and a music-streaming site, Xiami. Alibaba has also started to compete with Baidu, China’s leading search portal, by developing a search engine specifically for mobile, via a venture with UCWeb-browser, an already popular Chinese mobile browser.

Financial services

Alibaba’s Small & Micro Financial Services Group launched in 2010. By last summer it had issued more than 100 billion yuan in loans to some 320,000 small businesses, using data gathered on its e-commerce platforms to evaluate credit risk.

And then there’s Yu’e Bao. Run through Alibaba’s online payment platform, Alipay, Yu’ebao lets customers invest in a high-yield money-market fund managed by Tianhong Asset Management, and now has more investors than China’s stock markets. Alibaba’s small and micro financial services group is currently seeking a controlling stake in Tianhong. Meanwhile, China’s banking regulator recently gave Alibaba approval to launch a private bank designed to channel loans to small, non-state companies.

Along with Alipay, these new financial-services businesses are unlikely to be part of the listed entity. (Keeping those divisions separate may be why last month, a company owned almost entirely by Ma paid 3.3 billion yuan for a controlling stake in Hundsun Technologies, a securities-trading software firm.) However, they’re a crucial part of the larger Alibaba strategy.

Education

Alibaba Group joined Temasek and other prominent funds in February to invest $100 million in TutorGroup, an English-learning tutoring platform that connects students in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan with more than 2,000 teachers in 30 countries. TutorGroup is now expanding beyond English-language tutoring and into 40 countries worldwide. It’s not clear how large Alibaba’s stake is.

Travel

As domestic and international tourism has taken off in China, Alibaba launched a travel section of its marketplace, Taobao Travel, where travel operators offer flights, hotels, tours and other packages. The company has also invested in a Chinese portal, Qyer, for travel deals, and a travel journal app called 117go (like Instagram, but exclusively for travel). It has also led funding for a visa services company called ByeCity.

Retail logistics

As an e-commerce company, Alibaba needs to ship goods to far-flung corners of China with poor infrastructure. Late last year it bought a $364 million stake in Chinese appliance and logistics company Haier. The deal establishes a joint venture with the Haier subsidiary Goodaymart, which has a network of 20,000 stores and distribution channels in some 2,800 Chinese counties that Alibaba can use.

In March, Alibaba also made its first foray into brick-and-mortar stores, buying a minority stake in the Chinese department store operator Intime. The goal is to build up “online-to-offline” shopping—a sector that accounted for only 1.2% of all e-commerce transactions last year. Intime will encourage customers to use QR codes and virtual prepaid cards offered by Alibaba to make purchases in its stores, while Alibaba will sell Intime products on Tmall.

Cloud services

Alibaba launched its cloud service in 2009 under the moniker Aliyun or Alicloud. Shortly after acquiring Dropbox-clone Kanbox, in September 2013, Alibaba announced plans to launch Aliyun worldwide starting this year, with hints that it will focus on the US and Southeast Asia. Alibaba is squaring off against Amazon Web Services, the current leader in rented cloud computing, which recently started expanding into China.

Going global

Though Alibaba has the corner on China’s rapidly growing e-retail sector, its ambitions are bigger. In September 2013, it launched Taobao in Singapore, which will serve as its Southeast Asia hub.

But it also has its sights set on the US. Since the beginning of last year, Alibaba has been on a global shopping spree, buying stakes in a slew of US startups and launching 11 Main, a US online retail site, in February 2014. Its investments include 1stdibs, a luxury e-commerce site; Tango, a WeChat-like mobile messaging app; ShopRunner (paywall), a storefront-based online shopping platform; Quixey, a mobile search company; Fanatics, a sports e-commerce company; and Lyft, a US ride-sharing app that’s one of the main competitors to Uber.